What’s At Stake?

Politically Charged Public Art in the 2020s

Written by Vibeke Christensen og Tina Skedsmo

Overtly political contemporary art and conflicts of opinion are both vital elements in a modern, democratic society. Ephemeral public art projects bring the possibility of pronounced actuality. Art’s essence is freedom of speech and as such, defending its autonomy is a democratic responsibility. Yet how do we as public art producers and curators navigate a situation of increased geopolitical mistrust, harassment of artists, and rapid digital dissemination with real world impact? How do we sustain art’s autonomy and respond to art’s influence on our conceptualization of the world and ourselves?

In this essay we investigate what scope of possibility public art has to raise politically charged questions in our society today by looking into two ephemeral art projects curated and produced by Kulturbyrået Mesén. In both these art projects, separating art and artist is almost impossible. Gelawesh Waledkhani (b. 1982) and Ahmed Umar (b. 1988) bring their personal histories into their artworks, undeterred by forces seeking to silence them. Born in Kurdistan and Sudan respectively, both Waledkhani and Umar came to Norway as refugees. As the artistic project is interwoven with individual battles of resistance and emancipation, the two artists manage to address issues of freedom of speech and identity in a way only they can: their narration is their own, the emanating voice deeply personal and the gaze direct. Still, the issues the artworks touch upon are global in outreach and potential impact. The political has now become deeply personal.

Visibility and Discourse

Waledkhani’s Rojava: The Women’s Revolution and Umar’s Carrying the face of ugliness are ephemeral art projects produced in public places in Oslo, Norway. The temporary nature of these projects renders them especially equipped for raising questions of current interest. Particularly at Oslo Central Station we have the possibility to swiftly showcase artworks of impassioned topicality, for instance by re-curating already existing works as we did with Umar’s Carrying the face of ugliness during the fall/winter 2022. The exhibition space in Rosenkrantz’ street however, is a six-metre wide wall for showing original artworks, oftentimes produced in situ. This wall is reserved for art that encourages freedom of speech and public debate. Here, Waledkhani’s Rojava: The Women’s Revolution was shown in 2020.

Temporary artworks provide opportunities that permanent works do not. For instance, there are fewer considerations concerning maintenance and the range of possible materials is drastically expanded when decay and decomposition are not an issue. Especially when working in public space, ephemerality could be both a quality and a method. Without anyone owning the work, the artist may be more daring in subject matter as well as choice of material. Knowing the artwork will eventually be removed, artists can take a greater risk both concerning their oeuvre and the statement they are making. Especially important for artists and curators working in the public space, ephemerality brings the possibility of to work with very timely subjects.

As the advertisement industry has clearly demonstrated, visual images influence our conduct and beliefs. In the exhibition arena in Oslo Central Station where visitors amount to some 150.000 each day, the mere volume of visitors demarcate the art projects as influential. Public space, physical as well as digital, is «permeable, both bounded and unbounded, local and global, contested, mutable and socially contingent»¹. The text seeks to demonstrate the potential impact, consequences, and outreach of art in public places. By reference to Waledkhani and Umar’s separate artworks, the text will prove how art in public places is political, “never simply decorative”.²

Public art exists within a discursive urban context. Discourse, as it is inseparable from the duality of utterance and silencing (production and repression of “truth”), relates to power as either instrument, effect, or hitch. Furthermore, discourse’s knowledge production makes up the foundation for authorisation and execution of power. Therefore, the struggle to break free from the system for signification (oppression) is essentially situated in the language of discourse, i.e., the space in which conversation can happen. It is also the space in which we, as producers and curators of public art, facilitate certain expressions, in certain sites. Thus, public space, providing specificity of site to public art, must be understood “to encompass the individual site's symbolic, social, and political meanings as well as the discursive and historical circumstances within which artwork, spectator, and site are situated”.³

Furthermore, as the world has become more globalised and people share and discuss art and politics online, artworks sometimes take on their own life. The context in which art is reproduced, shared, and debated both online and in the media entails both increased visibility and international impact as well as threats of violence and silencing, menacing freedom of speech and democratic values.

Rojava. The Women’s Revolution

In Gelawesh Waledkhani’s monumental drawing Rojava: The Women’s Revolution (2020) seven women stand out against a plain white background. The intricate, black lines of the felt pen give form and movement to the women's jackets. Formally, the composition is split horizontally in three: the first dividing line following their shoulders, separates the black and white clothing and equipment from the lighter, softer rendering of the heads and faces with their colourful headdresses. The third, upper part consists of a single quotation in red letters: “A society can never be free without women's liberation.”

Against the monochrome of the women’s torsos, the headdresses are important in providing each represented woman an distinct identity. The gaze directed out of the picture frame arrests the beholder as the woman becomes the individual face of the revolution.

Gelawesh Waledkhani, Rojava: The Women’s Revolution, 2020 (detail). Photo: Vibeke Christensen, Kulturbyrået Mesén.

The women’s torsos melt together, forming one large, communal shape. The slings crisscrossing their bodies further accentuates the formal compactness and simultaneously signifies the lethal bond between the women. These women are taking to arms against the terrorist organisation IS (The Islamic State) in Rojava, on the Turkish-Syrian border, in Western Kurdistan. The ongoing revolution calls for democratic autonomy, peace amongst religious groups, and equal rights for women. Waledkhani’s group portrait is a representation of real women she has met, proclaiming the extensiveness and importance of a distinct female fight of resistance amongst Kurdish people. In 2015, the year of the famous battle of Kobane in Rojava, Evangelos Aretaios wrote from his visit to the front:

In the wider Middle East since the nineteenth century and before that, the female body is one of the most important symbolic battlegrounds between modernizers and reactionaries. Today, here in Syria, this fight is to death.⁴

Waledkhani’s monumental drawing highlights the weighted importance the women play in the revolution and the quote “A society can never be free without women's liberation” speaks of the Kurdish commitment to found a democratic, autonomous administration in which women and men are equals. The extensive focus on gender equality that characterises the revolution, is largely based on the writings of author and philosopher Abdullah Öcalan (b. 1948) who Waledkhani quoted in red, large letters in her artwork for Rosenkrantz’ street. Öcalan, having founded the PKK (The Kurdistan Workers' Party) in 1978, is facing a life sentence in Turkish prison being labelled a terrorist, yet his writings on decolonization, democracy and gender equality continue to influence the Kurdish resistance and spark hope of a different reality amongst the women fighters at the front. The weapons that the women in Waledkhani’s drawing are carrying, demarcate the role of the woman in the life-and-death fight for freedom in Kurdistan, and symbolise ideological convictions challenging patriarchal views on gender in radical ways. Facing threats of slavery, sexual violence and death, these Kurdish women are reclaiming the power of the female sex, also taking advantage of the IS’ fundamentalist belief that whoever is killed by a woman is not allowed into heaven.

The gaze directed out of the picture frame arrests the beholder as the woman becomes the individual face of the revolution, evoking pathos by virtue of the graveness of expression and demanding accountability. It is a gaze refusing the categorization of a patriarchal system for signification, a symbol of the women reclaiming the power to act on their own terms – even in the face of death.

The swirling lines of the felt pen bear witness to a particular movement of the hand, an expression of a female artisan tradition. The weapons demonstrate the role of the woman in the fight for freedom in Kurdistan, and symbolise ideological convictions challenging patriarchal views on gender in radical ways. Gelawesh Waledkhani, Rojava: The Women’s Revolution, 2020 (detail). Photo: Vibeke Christensen, Kulturbyrået Mesén.

The headdresses are colourful focal points. A piece of clothing as much as a symbol, the headdress becomes central in understanding conflicts of identity and freedom, inasmuch as it is impossible not to read today without referencing the ongoing revolution in Iran. Against the monochrome of the women’s torsos, the headdresses are important in providing each represented woman with an individual identity. Noticeably, everyone wears it in a different manner and one woman has removed it. This leads us to inspect the headdresses more carefully, both what is actually represented and what is covered up. As such, the stand-out pieces of clothing turn into a play on cover and reveal, a formal approach with a longstanding tradition in art history in the representation of the female body. Simultaneously giving symbolic form to a female reality where bodies are being dictated by others and demarcating the women themselves, as autonomous beings. Thus, it offers insight into ways of seeing, of the patriarchal gaze upon the woman.

In Waledkhani’s work, the woman who has taken the headdress off becomes a nexus where political ideology intersects with the life of a woman. The drawn lines of her hair merge with those of her skin, in a drawing technique that is a reference to Kurdish weaving tradition. The thin and swirling lines bear witness to a particular movement of the hand, an expression of a female artisan tradition.

The Controversy of a Word

Having utilised a quotation by the former leader of the PKK – importantly, never declared a terrorist organisation by Norwegian authorities – the artwork received a lot of media attention and overwhelming negative response from Turkey. The Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs demanded the municipality remove the artwork, proclaiming Oslo was supporting terrorist propaganda. Likewise, the Turkish ambassador in Norway Fazlı Çorman called it an “insult,” also stating the municipality is being “used by supporters of the Norwegian branch of the PKK”.⁵ This seems to indicate that both artist and curator are PKK supporters, which would be a serious and ill-informed opinion of the professionalism of both Kulturbyrået Mesén and the broader extent of the Norwegian art field. Not only is this a statement ignoring the artistic process as a whole, but it fails to understand the curatorial process as transparent and democratic.

The Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs demanded the Oslo municipality remove the artwork after having painted the words of Abdullah Öcelan. As a writer and philosopher, his writings reference the Kurdish words jin meaning woman, jiyan meaning life, and azadi meaning liberty.

Gelawesh Waledkhani, Rojava: The Women’s Revolution, 2020. Photo: Vibeke Christensen, Kulturbyrået Mesén.

However harsh the rhetoric and great the Turkish efforts to have the artwork removed, 3 February 2021 Oslo Culture Committee declined their demands, unequivocally supporting Waledkhani and freedom of expression. Ambassador Çorman then wrote a letter to all 59 members of the Oslo City Council, asking them to “correct the city authorities’ inconsiderate support and glorification of terrorism”.⁶ 17 January 2021, Oslo City Council unanimously voted the artwork remain on show with Vice Mayor for Culture and Sports Omar Samy Gamal calling freedom of speech “a pillar in a free democratic society”.⁷ Waledkhani also received joint support from Association of Norwegian Visual Artists (Norske Billedkunstnere), Young Artists’ Society (Unge Kunstneres Samfund) and The Center for Drawing (Tegnerforbundet).⁸

Even though Öcalan is a controversial person, the quote is universal. Speaking on behalf of all oppressed women, the wording should not be contentious. However, in the ears of some men/regimes the quote in itself becomes problematic. In 2020, one would think that acknowledging women’s place in a free society would be indisputable but unfortunately, the reality is that women’s liberation is controversial in many places still today.

Once more, we witness a displacement of focus, from the women depicted onto the man, referenced. As such, Turkey’s arguments and the larger debate is based, predominantly, on an abstraction of artistic content. As Waledkhani herself has stated: “My artwork, which the Turkish government is trying to remove, is meant as a message to all the women of the world that fighting for one’s rights is worth it”.⁹ Rojava: The Women’s Revolution is a portrait of women, an artwork on its own terms yet an opportunity for marginalized voices to assert themselves.

The demand to remove the artwork should therefore also be understood as a refusal to relate to that which is actually represented and interpret it within the frame of reference that is the canvas. Noticeably, it is an unwillingness to respond to the artwork as art – intrinsically autonomous – but rather deem it a solely political manifestation.

Öcelan’s writings uphold the philosophy of Jineology that finds its point of reference in the Kurdish words jin meaning woman, jiyan meaning life, and azadi meaning liberty. It is a philosophical orientation and a movement claiming to build democracy, socialism, ecology, and feminism. Should we not be able to view Öcelan’s quotation in regards to his work as an author and philosopher, in the same manner that we not only tolerate but are able to praise the work of Knut Hamsun, even though his affiliations with the nazi cause is widely known? Taking the literary object as a starting point and investigating Öcelan as an author and feminist philosopher, may bear fruit of insight and empowerment beyond a black-and-white picture of violence.

Yet, the nature of public art challenges the borders of autonomy and discourse. As public art «defines and makes visible the values of the public realm, and do so in a way which is far from neutral, never simply decorative», the artwork has a clear political side.¹⁰ That side however, need not be a direct utterance of support or rejection to any political movement as such. The debate that arose as Waledkhani’s artwork was exhibited in Rosenkrantz´street shows that even today, merely arguing the freedom of art in the public space is a political statement. The fact that a single quotation within an artwork has generated such strong reactions shows the power of definition inherent in art. Art’s essence is freedom of speech and as such, defending its autonomy is a democratic responsibility.

Waledkhani touches upon this when she writes of Turkey’s reactions to the artworks as “nothing but an attack on the freedom of speech”.¹¹

Art and Geopolitical Unrest

The core of the matter then is not only protecting freedom of speech, but also actively providing space for speech. In turn, this will not diminish the right but enforce it. Both challenging contemporary art and conflicts of opinion are vital elements in a modern, democratic society.

Waledkhani undoubtedly risks a lot by exhibiting Rojava: The Women’s Revolution, even in Norway where freedom of speech is protected. In fact, constitutional protection of human rights, gender equality, transparency, and democracy are characteristic of the Nordic countries. Yet, in the mind of Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, it is a terrorist hotbed. Ambassador Çorman’s accusation of the municipality acting in the PKK’s interest speaks of such geopolitical mistrust.

When the Swedish and Finnish NATO bids were blocked by Turkey, Waledkhani’s artwork resurfaced in the news, manifesting its transnational impact. In July 2022, Aftenposten wrote: “When Erdogan speaks of the Nordic countries and Norway as nests of terror it is reasonable to believe he refers to Kurdish groups. It is the opinion of the Turkish government that groups supporting the PKK are allowed to operate too freely. They do not like what they consider to be obvious support of the PKK founder Abdullah Öcalan.”¹²

Carrying the Face of Ugliness

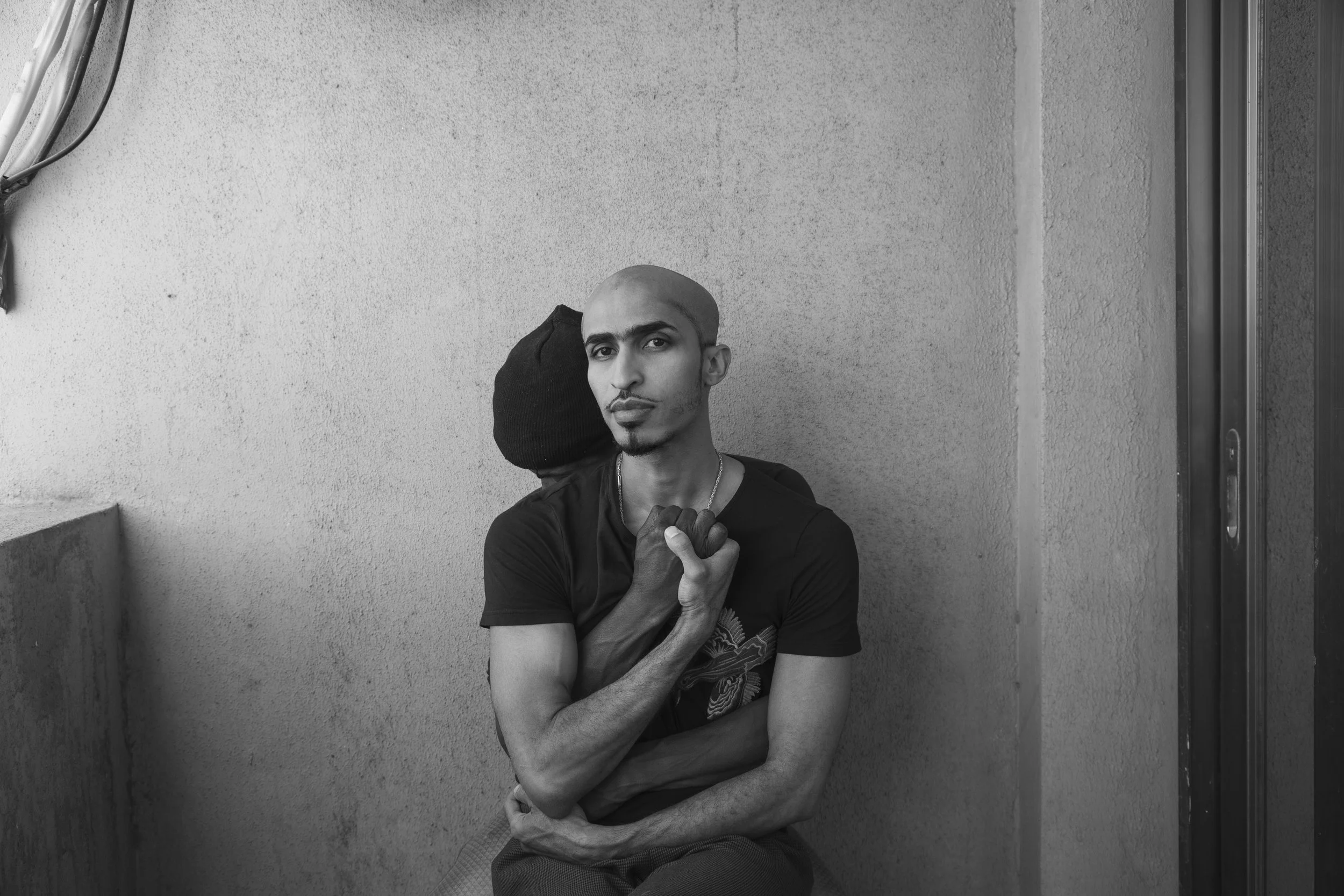

The images making up Ahmed Umar’s photo series Carrying the Face of Ugliness are portraits of people that are not allowed to live as their true selves. The eight black-and-white pictures, of which four were shown in Oslo Central Station, Ski Station, and Oslo Airport Station show the artist standing in front of the person actually being portrayed. The gesture is bold, powerful and raw in expression, and blown up to 10 x 10 metres makes a monumental impact on the square.

Umar’s portrait of Mina, 33 years old. In lending his face to his subjects, Umar gives a face to the struggle for queer rights on behalf of people who are silenced, unable to stand up for themselves.

Ahmed Umar, Carrying the face of ugliness, 2018. Photo: Kulturbyrået Mesén

In 2018, Umar travelled back to his native Sudan and met people from LGBTQ+ community prohibited from living openly as their true selves. Until 2020, homosexuality was punishable by death in Sudan. Although never put into practice, the law still resulted in people being assaulted. The people Umar are portraying risk social stigmatisation, isolation, persecution, and death. Inspired by the Sudanese saying “carrying the face of ugliness,” meaning confronting an issue and taking on the blame for others, he decided to do a series of portraits within the community. In lending his face to his subjects, Umar gives a face to the struggle for queer rights on behalf of people who are silenced, unable to stand up for themselves. In some photos, Umar is dressed in some of the subjects’ personal items, or their hands lock in a clutch so intense it can be read as connoting the violence of the regime. The portraits show individual gestures of love, fear, and resistance together with Umar’s protective presence, a brave stand in for a burden shared. His powerful gaze directed towards the beholder forces us to take their cause to heart.

The backgrounds are simple, consisting of concrete walls and sometimes a square window centred in the composition. The formal contrast to the organic lines of the human body is striking. It is a document of the conditions in which the pictures were taken: on private property, against hard walls with closed shutters bringing associations of having to hide. The idea of a lack of freedom, of a world not willing to accept diversity – effectively grey – and of small-scale resistance looms within the image.

There is a duality in the portraits, a shift between strength and vulnerability, individual expression and anonymity. This is true also of the accompanying texts where everyone depicted is given the chance to tell their story, their fears and hopes for the future.

In a simultaneously, visceral and poetic way, Umar’s Carrying the face of ugliness is able to say something about what is at stake: both the brutal realities marking the everyday life of his subjects and that which queer people all over the world face every day. Their stories concern us, on a both national and global level, and demonstrate how we might find hope and strength in each other’s experiences.

Umar’s portrait of Hamza Mustafa, 28 years old. There is a duality in the pictures, a shifting forth between strength and vulnerability, individual expression and anonymity.

Ahmed Umar, Carrying the face of ugliness, 2018. Photo: Ahmed Umar.

Erasing a Face

In January 2023, two of Umar’s photographs exhibited in Oslo Airport Station were subjected to vandalism. The person(s) responsible had deliberately cut/torn out the parts of the picture showing Umar and the other two subjects. It is not known who did it or why, but the erasing of the people and not other parts of the images surely means the damage was intentional. The vandalised artworks provoked a sad and ghostly feeling, not at least because the elimination of the subjetcs within the portraits evokes the violence and persecution of queer people. Furthermore, on the opening night of the exhibition in September 2022, Umar was confronted by an enraged man telling him to “respect” the laws of Sudan, responding with agitation to both the accompanying texts, the pride flag, and Umar’s speech. Instances such as these speak of the risk of harassment Umar and Waledkhani are facing every day, and also demonstrate how public space in Norway is challenged; how freedom of speech is still contested. The Turkish mass reaction and the anonymous vandalism are two very different attempts at reducing the space for others, threatening the scope of possibility for the politically charged public art and surely making us consider our incentives and risks.

Umar’s portrait of Hamada, 24 years old, vandalized in Oslo Airport Station.

Ahmed Umar, Carrying the face of ugliness, 2018. Photo: Vibeke Christensen, Kulturbyrået Mesén

Politically Charged Public Art Today

Both projects touch upon some key issues concerning art in public places – from the production to the encounter with the work. Seeing how artists are facing backlash like this, the curator and producer of art in public spaces must investigate and define their own role. As tendencies in our contemporary world are seeking to narrow the scope for expression within public space, navigating the discourse and managing public art projects grows more complex. What is the scope of possibility for politically charged public art today? What do we actively make space for, and what do we passively accept? Where do we draw the line, and who’s hand is guiding the pen?

Precisely because public art in a way imposes itself on the public, the mechanisms for producing it have to take into consideration the many facets of urban life and adapt for multifarious readings or experiences with the artwork. Public art «is not only the private expression of an individual artist; it is also a work of art created for the public, and therefore can and should be evaluated in terms of its capacity to generate human reactions».¹³ This touches upon public art’s importance but also its challenges. Within a context of increased political tension, the freedom of speech and artistic expression are simultaneously more important and fragile than ever. As the risks that the artists are facing turn more perilous, how do we sustain their incentives?

In the broadest sense, artistic productions and the discussions that arise around them in the urban space – «never successfully colonised as an art space» – are political.¹⁴ Both Rojava: The Women’s Revolution and Carrying the face of ugliness are able to say something about the conditions for freedom of speech today. As they thematise suppression and acceptance, they also touch upon the vulnerability of political systems. Umar lends his face to individuals and collective struggles; they belong to the ones portrayed, yet the values they are fighting for are global. Umar even dreams of organising the first ever pride parade in the Arab world, in Khartoum in 2030. In a similar way, Waledkhani’s solidarity act is giving a collective battle its individual faces, and taking on a voice for those who are silenced. Although both artworks find their point of reference in Kurdistan and Sudan, and in the issues women and queer people encounter in those parts of the world, the challenges remain relevant in Norway, not to mention in a changing Europe.

Gelawesh Waledkhani (b. 1982) is born in Kurdistan and currently living and working in Norway. Her artistic project has a distinct humanist orientation taking on issues of feminism and human rights. In diverse media like embroidery, drawing, installation, and video she poetically handles themes of oppression and ethnic groups suffering the consequences of brutal wars. She is profoundly engaged in the marginalisation of the Kurdish people as part of a more extensive geopolitical game amongst world powers.

During the summer of 2018, Waledkhani travelled to Rojava (West Kurdistan) in North East Syria where she worked with children in refugee camps. Since 2017, she has introduced contemporary art to children in Norwegian reception centres through creative workshops.

Photo: Jannik Abel/Høstutstillingen

Ahmed Umar (b. 1988) came to Norway from Sudan as a political refugee in 2008. Since then, he has finished a master’s degree in Medium and Material based Arts from the Oslo National Academy of the Arts. In his art, Umar investigates the relation between gender, sexuality, power, and art. He works in ceramics, textile, graphics, photography, and performance and is inspired by Sudanese art and heritage, especially that which has been preserved by female artisans.

Photo: Ahmed Umar

¹ Hall and Robertson, “Public Art and Urban Regeneration: advocacy, claims and critical debates”, 19-20.

² Miles, Art, Space and the City. Public Art and Urban Futures, 61.

³ Deutsche, “Uneven Development: Public Art in New York City”, 14.

⁴ Aretaios, «The Rojava revolution».

⁵ Ekroll and Ask, «Tyrkias ambassadør i brev til bystyrerepresentanter: Ber politikere stemme for å fjerne kunstverk».

⁶ Ekroll and Ask, «Tyrkias ambassadør i brev til bystyrerepresentanter: Ber politikere stemme for å fjerne kunstverk».

⁷ The Department for Culture and Sport, “Vedr. innbyggerforslag av 15.11.2020 - Kunstverk støttet av Oslo kommune - uttalelse til kultur- og utdanningsutvalget”, 08.01.2021); Kulturbyrået Mesén, «‘Et samfunn kan aldri bli fritt uten kvinnefrigjøring’».

⁸ Norske Billedkunstnere, Unge Kunstneres Samfund and Tegnerforbundet, «Til støtte for Gelawesh Waledkhani: ‘Det er avgjørende at bystyrepolitikerne nå viser at de verner om den kunstneriske ytringsfriheten, og at kunstverket får bli hengende’».

⁹ Waledkhani, «Kunstverket er et budskap til alle kvinner: Det nytter å kjempe for sine rettigheter».

¹⁰ Miles, Art, Space and the City. Public Art and Urban Futures, 61.

¹¹ Waledkhani, «Kunstverket er et budskap til alle kvinner: Det nytter å kjempe for sine rettigheter».

¹² Aukrust, «Erdogan stempler de nordiske landene som ‘terror-reir’».

¹³ Cohn, “As Rich as Getting Lost in Venice: Sustaining a Career as an Artist in the Public Realm”, 177.

¹⁴ Miles, Art, Space and the City. Public Art and Urban Futures, 15.

Bibliography

Aretaios, Evangelos. «The Rojava Revolution.» Open Democracy. 15.03.2015.

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/north-africa-west-asia/rojava-revolution/

Cohn, Terri. «As Rich as Getting Lost in Venice: Sustaining a Career as an Artist in the Public Realm». In The Practice of Public Art, edited by Cameron Cartiere and Shelley Willis, 176-192. New York and London: Routledge, 2008.

Deutsche, Rosalyn. “Uneven Development: Public Art in New York City”. October 47 (1988): 3-52.

Ekroll, Henning Carr and Alf Ole Ask. «Tyrkias ambassadør i brev til bystyrerepresentanter: Ber politikere stemme for å fjerne kunstverk.» Aftenposten. 12.02.2021. https://www.aftenposten.no/oslo/i/WOkov2/tyrkias-ambassadoer-i-brev-til-bystyrerepresentanter-ber-politikere-stemme-for-aa-fjerne-kunstverk

Hall, Tim and Iain Robertson, «Public Art and Urban Regeneration: advocacy, claims and critical debates». In Landscape Research 26, no. 1 (2001): 5-26.

Kulturbyrået Mesén. «‘Et samfunn kan aldri bli fritt uten kvinnefrigjøring’.» https://www.mesen.no/aktuelt/et-samfunn-kan-aldri-bli-fritt-uten-kvinnefrigjring

Miles, Malcolm. Art, Space and the City. Public Art and Urban Futures. London: Routledge, 1997.

Norske Billedkunstnere, Unge Kunstneres Samfund and Tegnerforbundet. «Til støtte for Gelawesh Waledkhani: «Det er avgjørende at bystyrepolitikerne nå viser at de verner om den kunstneriske ytringsfriheten, og at kunstverket får bli hengende.» 13.01.2021. https://www.norskebilledkunstnere.no/aktuelt/det-er-avgjorende-at-bystyrepolitikerne-na-viser-at-de-verner-om-den-kunstneriske-ytringsfriheten-og-at-kunstverket-far-bli-hengende/

The Department for Culture and Sport, “Vedr. innbyggerforslag av 15.11.2020 - Kunstverk støttet av Oslo kommune - uttalelse til kultur- og utdanningsutvalget”, 08.01.2021.

Waledkhani, Gelawesh. «Kunstverket er et budskap til alle kvinner: Det nytter å kjempe for sine rettigheter.» 27.01.2021. https://www.aftenposten.no/meninger/debatt/i/2dP45R/kunstverket-er-et-budskap-til-alle-kvinner-det-nytter-aa-kjempe-for-sine-rettigheter

Aukrust, Øyvind. «Erdogan stempler de nordiske landene som ‘terror-reir’.» 20.07.2022. https://www.aftenposten.no/verden/i/Jxkbg7/erdogan-stempler-de-nordiske-landene-som-terror-reir